Refugees from the Camp Fire in Cayucos

February 24, 2020

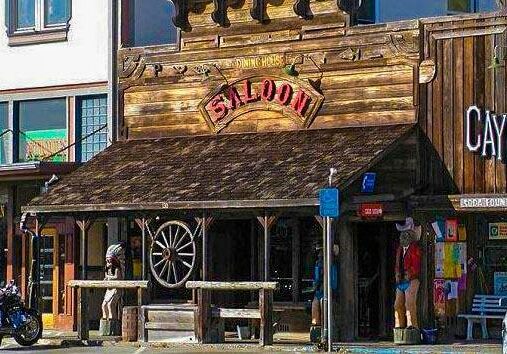

Cayucos Tavern

Editor’s Note: The following series, “Life in Radically Gentrifying Cayucos by the Sea,” to be posted biweekly includes the notes, thoughts, and opinions of an original American voice: author Dell Franklin.

By DELL FRANKLIN

You don’ expect to run into people on the beach whose lives have been disrupted and maybe ruined by the worst fire in the history of California, a state that seems to be an ongoing tinder box. I was on the beach with Wilbur after moving through the area between the Cayucos Motel and the Shoreline Inn, when I spotted a man sitting by himself in a beach chair gazing out at the ocean at around 5 in the afternoon; a magical time in Cayucos, when the quality of light burnishes the sand in a golden haze. Windless, benign, the ocean slick and gleaming, a stillness settled over a beach made expansive by the tide flowing far out, further isolating the man sitting on his chair sipping a beer.

A good guess was he was staying at the Shoreline. My old brown Lab was soon nudging him for a pet.

And he complied, telling me his Golden retriever had died a few weeks past and he was finished with dogs. He said this was his first visit to Cayucos, though he’d wanted to come here all his life but never got around to it, and was originally from the fringes of Santa Maria in what is now Orcutt—an area he now avoided.

We talked about how relaxing and sedate, even tranquilizing Cayucos was, and soon I got around to asking him where he was from.

“I really don’t live anywhere,” he said. “My wife and I are in limbo. We lost everything in the Camp Fire.”

“Everything?”

“Everything. Burned to the ground. Not one thing.”

“Paradise?”

“No, Concow, a little country town a few miles away—burned to the ground. Erased.”

He was probably in his sixties, with a neatly cropped gray beard and short white hair. I tried to imagine what it would be like if everything I owned and my beloved Cayucos was burned to the ground, like little beach towns vanishing in the horrific blazes going on in Australia. Where would I go? What would I do? How would I feel? Unimaginable.

“Losing everything’s got to be stressful,” I said. “It’s got to be beyond stressful.”

“Tell me about it.”

At this point a haggard woman of about 60 showed up and said to him, “Where’s my chair?”

“Sorry hon, I forgot. You can have mine.”

“It’s okay.”

I looked at him, then her. “That kind of stress, it has to affect your health, physically and mentally.”

“How about a heart murmur,” the lady said, touching her chest. “Among other things.”

They both had the ragged look of people who don’t sleep much.

“I’ve gotten diabetes,” he said. “It breaks down your health, losing everything, being suddenly homeless, it takes everything out of you.”

I said, “There’s so much media coverage of these fires, and especially that fire, and there’s all the tragic human interest stories and so on, but then it goes away, we forget about the long term aftermath. We lose track…but the damage, it goes on, huh?”

The lady nodded. She stood beside him. “It doesn’t go away. It never will.”

“What about insurance?” I asked.

“We got fully paid off,” he said.

“But it’s not enough to start over, build a home anywhere, really,” she said.

“We could buy a mobile home to live in, a big RV, but you’re not permitted to put it on your property as a home and live in it,” he said. “We’re living up on Highway 7 in the Sierras right now. In a shack. It’s pretty hard to live in California with what we have, losing everything. It’s too expensive. It’s impossible.”

They told me they were spared the worst of the horrors of the Camp Fire—witnessing it and fleeing from it and watching people suffer terrible ailments for life and even dying in it—because they were on vacation in Fort Bragg and read about it, knowing immediately that Concow was literally burned off the face of the earth.

“We went back when we could,” he said, finishing his beer. “There was nothing.”

“We’re better off than our friends,” she said. “Our health problems are from stress, not the trauma of seeing it and feeling it.”

“That has to be a horror story,” I said. “A constant nightmare.”

He nodded. “It’s bad enough as it is with us.”

At this point, Wilbur ceased nuzzling the man and wandered down toward the shore to approach a lady with two tiny dogs. I excused myself and wished them good luck. I visited with the lady for awhile and noticed the man left his chair and headed toward the Shoreline Inn, while his wife sat down.

I moved on to the pier, dawdled around, and wandered down the main drag past Cayucos Coffee, crossed the street and passed the Cayucos Tavern, and was at the corner across from the Brown Butter Cookie Company when I spotted the two refugees from the Camp Fire. They literally sprinted across Ocean Avenue towards the Tavern in a sort of joyous romp—like kids after school –then waved at me as they entered the pub.

That’s what I’d be doing.

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines