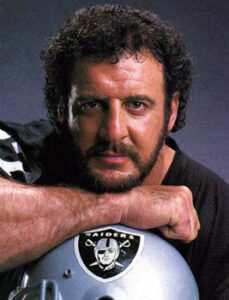

Young Howie Long on the hoop court

April 14, 2022

Dell Franklin

Editor’s Note: The following series, “Life in Radically Gentrifying Cayucos by the Sea,” to be posted biweekly includes the notes, thoughts, and opinions of an original American voice: author Dell Franklin.

Franklin’s memoir, “Life On The Mississippi, 1969,” is currently on Amazon.

By DELL FRANKLIN

Down in Manhattan Beach, a very large crew of us played hammer and tongs three-on-three basketball every Friday afternoon at 2 on the four hoops in the athletic complex of six tennis courts and two ball fields at Live Oak Park. It had been this way since I’d moved there in 1970, and the games had become more intense with an infusion of superior players and our own tournament twice a year — which drew players from other areas of LA.

It was 1984, and at around 3 p.m. on one of these Fridays, Howie Long of the LA Raiders and two teammates, Lyle Alzado and another even bigger moose, showed up at Live Oak, which had become a South Bay hoop Mecca by this time, and called winners on court one. And it just so happened that I was holding court one along with my two team mates, E Randolph Larson and my roomy Richard “Horse” Van Horson. All the other games were going on as we had just polished off our opponent when Howie showed up to challenge court one.

I stepped up and pointed down to court four, where an intense game was going on, because a team of three was warming up for a challenge, and once you lost on court four you had to wait. If you lost on court one you went down to court two, and so on. If you won, you climbed.

Lyle Alzado

“You have to call winners down there on the losing court,” I explained as tactfully as I could. “That’s court four.”

“Why can’t we start here?” Howie asked, as Alzado, perhaps the roughest defensive tackle in the NFL looked on and the towering moose scowled at me like he’d like to ring my neck. Howie was regarding me with a kind of sarcastic leer, and I’m sure he felt I knew who he was, and I did, because he had come into Brennan’s Irish Pub where I tended bar with a couple team mates (he didn’t drink) and I had actually discussed with him his threat to become a boxer as leverage with the Raiders during contract negotiations. I warned him that boxing was different, and a guy my size (185 pounds) could smack him around like a stepchild. He had been very cordial and, of course, signed with the Raiders.

But now I had to explain to him why he had to start out on the flunky court when he was fast becoming a national football hero on the NFL’s most legendary wild and crazy team. “Because this is top court, winner’s court. You gotta start out on loser’s court if you show up in the middle of games. You don’t just walk on and claim top court. You gotta work your way up.”

The leer still on his mug, he said, “So why are you on top court?”

“We won.”

Larson, a 6 foot 5 string bean who’d played at Stanford and was one of the best players around, stood arms folded, insouciant, amused, while his roomy grinned. A few players on court two and three peered over between ball exchanges. “You’re pretty cocky,” Howie commented. “Who gives you the authority to make the rules around here anyway?”

“I’m co-commissioner,” I explained, pointing at Larson, who along with me made up teams and policed the courts, though I was the heavy, even if I was only 5 foot 11, while Larson was the diplomat. “Fridays start at 2,” I explained to Howie Long. “Larson there and I make up teams, and the best shooter on each team shoots free throws to see who starts on top court, and it goes down from there. That’s the way it’s been for the past 15 years or so, and that’s the way it stays.”

I’m sure he felt I had to know who he was. He was grinning at me like he could not believe what I was pulling off when Alzado, one of the most menacing and menacing-looking figures on earth, muscles a bulge in shorts and tank top, stepped forward and very humbly offered a huge paw.

“Hey,” he said with mock meekness. “I’m just a little Jewish point guard from Brooklyn…is it all right if I play, Mr. Commissioner?”

I shook the massive, gnarled paw that engulfed mine. “Of course you can, Mr. Alzado,” I said, nodding at Howie. “But you must know, I’m the only Jewish point guard around here, and I’m from down the road in Compton.”

Alzado nodded. “I understand completely, Mr. Commissioner, I wouldn’t dare invade your turf. After all, we’re landsmen.”

The three giants stood and peered around, taking in the situation. Then Howie looked me over, really smirking. “Well, looks like there’s a long wait, and I’m not sure we can play here without a true point guard anyway,” he said, glancing at Alzado. Then he narrowed his eyes on me. “We’ll be back.”

“You’re welcome any time, Howie,” I said, grinning at him, and Alzado winked and the other moose scowled as they walked off, and Howie nodded very slowly and kept his stare in a manner letting me know he would be back.

*********

And he did come back, either by himself or with a friend, some times a defensive back, like Van McElroy. He was actually, for his enormous trunk, very agile and a good player who tried to play the game correctly, had no ball-hogging ego, and went out of his way not to hurt anybody, because, tough as we were, nobody stacks up to an NFL football player, and especially an all-pro future hall of fame defensive lineman. At the same time, when Howie abandoned the low post, where he would back you down with his enormous girth and tree-trunk legs for a bank shot or lay-up, and drove to the hoop, nobody volunteered to take charge.

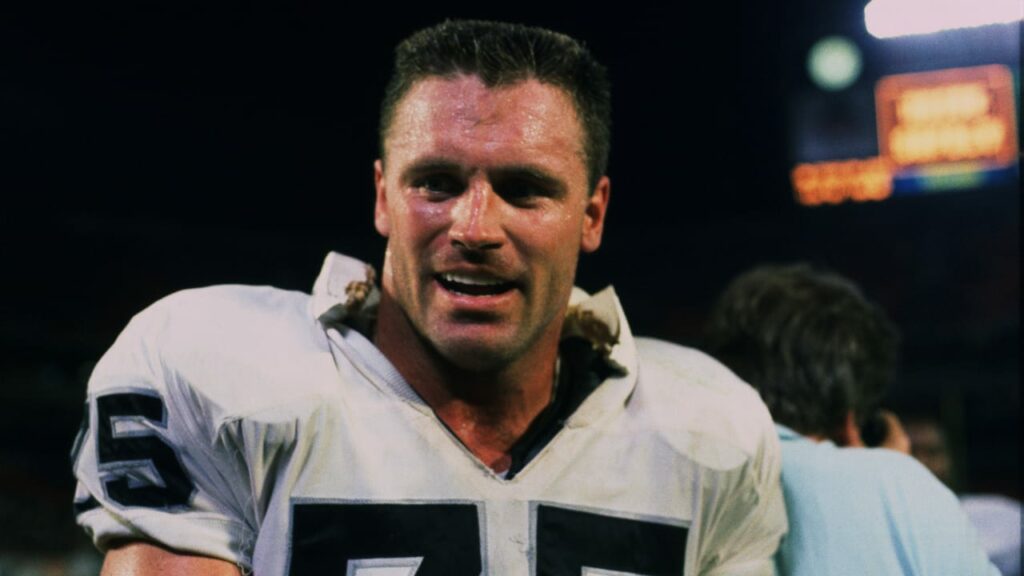

Howie Long

Not only did Howie acclimate himself to the games, he fit right in with the crew and became one of the boys. During the off-season, he adhered to our tribal rules unobtrusively. During breaks in the games, he sat along the fence bordering the tennis courts and talked to the lot of us about the Raiders, telling us how absolutely proud he was to be a member of this heralded team, and how fortunate he was to come from the Charleston area of Boston to actually get drafted out of Villanova and end up where he was.

One got the feeling the big man was in awe of his situation and still in disbelief of it, and especially the success of already being an all-pro and part of a Super Bowl victory.

At the same time, I felt there was no reason not to pick on him, and make him feel left out, especially since it was my nature to pretty much pick on everybody down at Live Oak Park because I ran things and was the oldest player and had grown up in a professional baseball player’s clubhouse and learned first hand the art of needling, the give and take of rough banter, a rite of passage among jocks and a forming of acceptance leading to camaraderie and long-held bonds of friendship.

Every once in a while, when Howie showed up, I’d say, “Maybe I’ll let you play today, Howie, if you behave yourself.”

He’d flash me the same look as everybody observed us, the gaze of a grizzly appraising a rabbit and deciding whether he was hungry or not. Once I told him, “Look at me, Howie, forty years old and not an ounce of fat. When you’re my age you’ll probably he 400 pounds and using a cane. Too bad you’re not me.”

He gave it back. I was regarded as an aggravating “flea.” Once I got caught on a mismatch off a pick, and ended up guarding him on the post, and when I hunkered down and shoved my forearm into his lower back, he sort of twitched his shoulder an inch or two and I went airborne and bounced off the chain link fence ten yards away. I ran right back and planted myself behind him and he snarled, “Get off my back, you little gnat, before I swat you.”

“I’m not a gnat,” I insisted. “I’m a killer bee.”

He let it go. Once, on another low post, I stripped him of the ball and he just stared at me, like this was the time he could actually exterminate me, but he said, very grudgingly, “Good hands.”

I decided not to rejoinder. But, as things went on, I continued the needling of Howie Long until one day my girlfriend at the time, Lita Colandrea, came over to my apartment and informed me of a conversation she’d had with Howie, who patronized the Criterion Diner in the heart of Manhattan Beach very early most mornings before continuing to El Segundo for practice.

Lita worked the 6 until 2 in the afternoon shift, and Howie got to know her by almost always sitting in her booth with two fellow defensive linemen. Lita owned the most ebullient personality in all of Manhattan Beach, was an institution at this diner and a sassy New Yorker with attitude and beauty, but no harshness and a great bawdy saloon-girl laugh. She said, “Howie Long was in this morning, and he asked about you.”

“Oh? What did he say?”

“He said, ‘that Dell guy, that old boozer from Brennan’s, says he’s commissioner of Live Oak Park, he’s your guy, huh? I told him yeah, he’s my man. Why? And he asks, do you cook, Lita, you know, cook Italian? And I said yeah, of course I cook Italian, and he says, so you cook for that old guy you say is your man? And I said sure, I cook for my man, and he says, Lita, I’m playing ball at Live Oak Park tomorrow afternoon, and I want you to cook for that old man tonight, because it’s gonna be his last meal. I’m going to exterminate him tomorrow afternoon.’”

Sure enough, he showed up. I didn’t say anything at first, but then, after a game or two, at the drinking fountain, I saw him staring hard at me a court or two over, and yelled at him, “You stop going into that goddam Criterion and terrorizing my woman, Long, or you’re gonna deal with me!”

He stared hard at me with that same old disbelieving leer, and then grinned, the same magnetic grin all football fans see every Sunday on the biggest football show in the land.

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines