Why is the Catholic Church celebrating genocide?

November 2, 2015

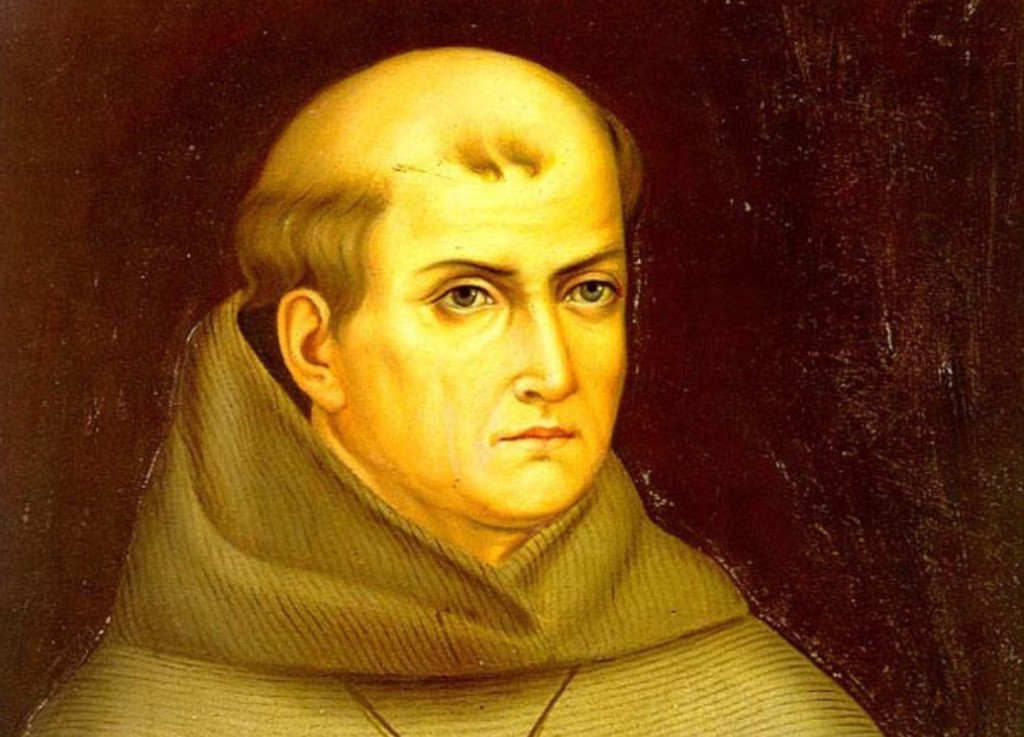

Junipero Serra

Opinion by José Freeman, Salinan Trowtraahl Elders’ Council

We are Salinan Trowtraahl. What we share here reflects solely and exclusively the heart of our Salinan village alone and not that of other Salinan tribal organizations.

Recently, we were invited to attend a mass in our homeland at Mission San Antonio which was built by our ancestors. The purpose of the mass is to celebrate the canonization of Junipero Serra. We responded to church authorities mainly with the following comments.

We see that the heart of individual Catholics is sincere in wishing for healing. However, healing requires acknowledgment of injury, admission of responsibility and a sincere effort at reconciliation through amends. This process is familiar to our native spiritual ethics. It is part of the Catholic Church’s Sacrament of Reconciliation. The Church in our area has yet to initiate true reconciliation.

Junipero Serra was the driving force for a system that brought severe and traumatic injury to the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being of our sovereign, native community. In 1980, local historian Olive Wollesen, who spent a good deal of her life getting to know Salinan people and history, wrote about us to linguist Dr. Katherine Turner that, “Accounts of genocide have been handed down by word of mouth in the Indian families.”

José Freeman

We do not use the word “genocide” lightly. However, our experience in the mission system fostered by Serra does meet the criteria for genocide as defined in United Nations Resolution 260 and adopted in 1948.

Particularly painful for our village upon hearing of Serra’s canonization was remembering the attitude he demonstrated toward the loss of so many young Salinan children to a plague at Mission San Antonio. On July 24, 1775, Serra wrote to Father Guardian Francisco Pangua, “In the midst of all our little troubles, which are plentiful, the spiritual side of all the missions is developing most happily. In San Antonio they are faced with two harvests at one and the same time, that is, of the wheat, and of a sickness among the children, who are dying.”

In effect, Serra was celebrating that a “harvest of the souls of children for God” had occurred at Mission San Antonio. Canonizing a man who rejoiced over the death of children before they even had a chance to live a full life is akin to ripping open the wound and pouring in salt. It is deeply painful for us to realize the Catholic Church would even consider celebrating the canonization of such a man.

We had hoped that the Catholic Church would not consider the death of innocent children to be part of their “mission to fulfill God’s command.” The cruelly insensitive canonization of Serra however feels typical of an institution that directly caused hundreds of thousands of deaths through 500 years of “Crusades” not to mention 200 years of Inquisitions.

There are those who say that the lives of native peoples in California were overall improved by the missions. From a strictly material perspective, life today does have advantages not previously available. However, what little we gained in the material sense pales in contrast to the psychological pain suffered by our families and the spiritual fragmentation of our community, culture and identity caused by genocide.

In Dec. 2007, retired Bishop Francis A. Quinn appeared at a mass at Mission of St. Raphael in San Raphael, California. He apologized to the Miwok Indians “for cruelties the church committed against them two centuries ago.”

Bishop Quinn further acknowledged that “the church authorities took the Indian out of the Indian, destroying traditional spiritual practices and imposing a European Catholicism upon the natives.” Those words were a beginning and a good first step in the right direction.

This most recent aggravation of our soul wounding by Pope Francis in canonizing Serra strengthens our resolve to continue putting the Indian back in the Indian.

José Freeman, 69, is a member of the Salinan Trowtraahl Elders’ Council who works as a marriage family therapist.

His father was born in 1900 and raised by his Salinan grandmother, Gertrudis Villavicencio-Soto, who was born in 1835. Gertrudis experienced the re-emergence of the Salinan culture at her uncle’s place, the Villa Ranch near Cayucos, after the missions were secularized in 1834.

Jose Freeman re-connected with the Salinan community in 1995 after being asked to research the history and culture for purposes of federal recognition. He continues to study and to be a part of healing from genocide through reawakening of the ancient culture’s traditions and language.

Find out what your neighbors think, like CalCoastNews on Facebook.

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines