A twisted road into the hands of a child rape suspect

July 30, 2015

Dee Torres-Hill speaking on behalf of CAPSLO.

By KAREN VELIE and DANIEL BLACKBURN

Editor’s Note: This is part two in a three-part series on how three children were taken from their parents and placed in a home with a man now accused of sexual assault. Find part one here.

Three San Luis Obispo children were taken from their homeless parents by the county’s Child Protective Service in 2002 and placed with a man now charged with rape, sodomy, and child molestation of the eldest child over a period of six years. The process that led to the removal of the children from their natural parents’ custody, placed them in foster care and eventually allowed them to be adopted by Robert John Bergner, 51, and his wife reflect a system lacking accountability and transparency.

Richard and Elizabeth Carroll left the Central Coast in the late 1990s. After living in North Carolina for four years, the couple moved back to the Central Coast in mid-2001 with their three children. At the time, the family lived out of an RV near Richard Carroll’s work at Mission Chevron while they searched for a new home. Elizabeth Cook was being treated for a bipolar disorder.

The couple sought housing from homeless services offered at the Prado Day Center by Community Action Partners of San Luis Obispo (CAPSLO). But after several weeks of participating in case management — which required the couple to give 70 percent of their $1,700 monthly income to be held for future housing — the couple asked to have their monies returned, according to court records.

On Dec. 11, 2001, Elizabeth Carroll took her three children to the Prado Day Center and treated her 5-year-old daughter for lice. As Elizabeth Carroll pulled out nits, the child cursed at her. Elizabeth Carrol then slapped her daughter, causing her nose to bleed.

Prado Day Center Manager Dee Torres-Hill then took the child into her office and called the police. San Luis Obispo Police Officer Mike Brennler arrived and Torres-Hill told Brennler the child’s mother had “punched” the child in the nose.

CAPSLO employee Bobby McDonald was the only other employee at Prado who supported Torres-Hill’s claim.

Brennler, a former mayor of Atascadero and now licensed private investigator, interviewed the child at the scene.

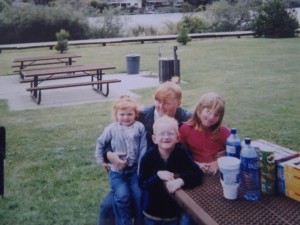

Elizabeth Carroll with her children in 2001.

In his report, Brennler said the child first repeated what Torres-Hill reported: That Elizabeth Carroll had punched her and in the past had spanked her younger brother.

The child then demonstrated the “punch” to Brennler showing an open-handed slap. Brennler determined, based on the child’s demonstration and “only very mild redness across the bridge of her nose” that she had been slapped, not punched, according to a police report dated Dec. 11, 2001. A physical check of the Carroll’s son also failed to support allegations of child abuse.

“I examined (child’s name) for evidence of child abuse, but did not notice bruises or abrasions consistent with child abuse,” Brennler said in the police report.

Nevertheless, Brennler decided to arrest Elizabeth Carroll, whose bipolar medication was being changed. Brenner said he wanted mental health services personnel to supervise the medication change.

“It should be noted that Elizabeth Carroll was cooperative throughout the incident, recognizing that she had acted inappropriately, and she also appeared remorseful for the behavior,” Brennler wrote in the police report. “Elizabeth Carroll also recognizes that she is in need of continued treatment by mental health.”

Two days after Brennler filed his police report, Torres-Hill called San Luis Obispo Child Welfare Services to make a statement. That statement, which differed from the police report, would be included in the official investigation narrative subsequently used to terminate the parental rights of Richard and Elizabeth Carroll.

“Dee said that both (daughter’s name) and (son’s name) said their mom punched (daughter’s name),” the Department of Social Services Dec. 18 narrative reads. “Dee heard Elizabeth’s explanation that it was a slap. Dee said she heard Elizabeth say she “hit her daughter because the bitch wouldn’t stay still.”

“Dee called (daughter’s name) into her office and asked her to demonstrate how mom had hit her. (Daughter’s name) punched Dee’s leg hard, with a closed fist. Dee also witnessed (daughter’s name) tell the police officer that her daddy hits her more than her mommy does.”

However, Brennler said the child didn’t say that her father hit her, something he would have been required to note in his report. A child’s statement about parental violence also would have required an investigation.

In the narrative, Torres-Hill also stated that even though she tried to walk the Carrolls thorough the process, the parents did not register their oldest child, a daughter, in time to attend the 2001/2002 school year. That statement would be repeated throughout court documents by social services workers.

In California, parents can in some cases elect to send their 4-year-old children to kindergarten. Nevertheless, the Carrolls decided not to have their daughter, who would not turn 5 until November, start kindergarten as a 4-year-old.

In addition, Torres-Hill said that the Carrolls were not treating the children for lice and that she had washed the oldest child’s hair herself several times and picked out the nits.

Multiple employees of the Prado Day Center and the Carrolls said lice was a major issue at that time in both the CAPSLO day center and at the night shelter. They said that Torres-Hill did not wash any of the clients’ hair herself.

“Dee never washed any of my children’s hair,” Elizabeth Carroll said.

Several former day center employees said they never witnessed the Carrolls abuse their children or fight amongst themselves, though they were aware Torres-Hill was upset with the family’s refusal to participate in case management.

“I never witnessed any abuse by the Carrolls,” said former day center supervisor Michelle Myers. “I knew Dee did not like the Carrolls.”

Several former employees also said Torres-Hill repeatedly called social services to investigate homeless parents.

“Dee would ask us to call CPS on clients for issues that should not have resulted in a CPS report,” said Joette Sunshine, a former day center employee.

After Elizabeth Carroll was arrested, Richard Carroll took several days off work to care for his children while he waited for his wife to return from county mental health. However, social services employees ordered him to begin raising his children as a single parent, Richard Carroll said.

On Dec. 14, 2001, Torres-Hill contacted county social services and said that Richard Carroll had mentioned selling his oldest child and that she was extremely concerned for the childrens’ safety, according to court documents.

“Reporting party (Torres-Hill) thinks the father is still hitting the children but being more secretive,” social services said in the Dec. 14 referral.

On Dec. 18, 2001, Torres-Hill asked Richard Carroll to come to the day center to discuss housing options, he said. But when he arrived at Prado, he was met by two social workers who said he could “do this the easy way or the hard way,” Richard Carroll recounted. He could get arrested while the allegations were investigated or he could agree to allow social services to take custody of his children during the investigation the social workers told him, Richard Carroll said.

Richard Carroll wept as he agreed to relinquish custody, according to court records.

Nevertheless, social services workers reported a different story in documents filed with the courts. Richard Carroll had relinquished custody of his children because he knew he was unable to care for them, the social workers wrote.

Social Services case workers then began a lengthy investigation into the childhoods of the Carroll parents. Neither had a criminal history as adults. County staff questioned the stability of Richard Carroll, noting that after his parents passed away when he was 11-years-old, he was placed in foster care.

In Aug. 2003, after foster parents Valerie and Robert Bergner said they were interested in adopting all three children, Superior Court Commissioner Sidney B. Findley terminated the parental rights of the Carrolls. His determination was based on court records that included Torres-Hills statements. In his ruling, Findley said he wanted the children to have better childhoods than their parents.

Get links to breaking news stories, like CCN on Facebook.

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines