San Luis Obispo’s affordable housing farce

October 30, 2019

Richard Schmidt

OPINION by RICHARD SCHMIDT

My fascination with tiny-houses-on-wheels goes way back, before that term existed.

Hippie vans of the late ‘60s and ‘70s lit the fire. Mass availability of vans was novel then, and kids quickly figured out they could become castles on wheels. With a whiff of incense and patchouli.

The open road beckoned, so why not travel turtle-style, with your abode on your back?

It wasn’t just vans, though. Resplendent with stylistic finesse, hippie gypsy wagons became updated 19th century prairie schooners. Pulled by a vehicle rather than oxen, they were often works of art, and are direct ancestors of today’s tiny-houses-on-wheels.

This was strictly do-it-yourself-type self-reliance, with a dollop of self-expression. There wasn’t an industry to build gypsy wagons. It was something you built yourself to express your notion what king-of-the-road life should be.

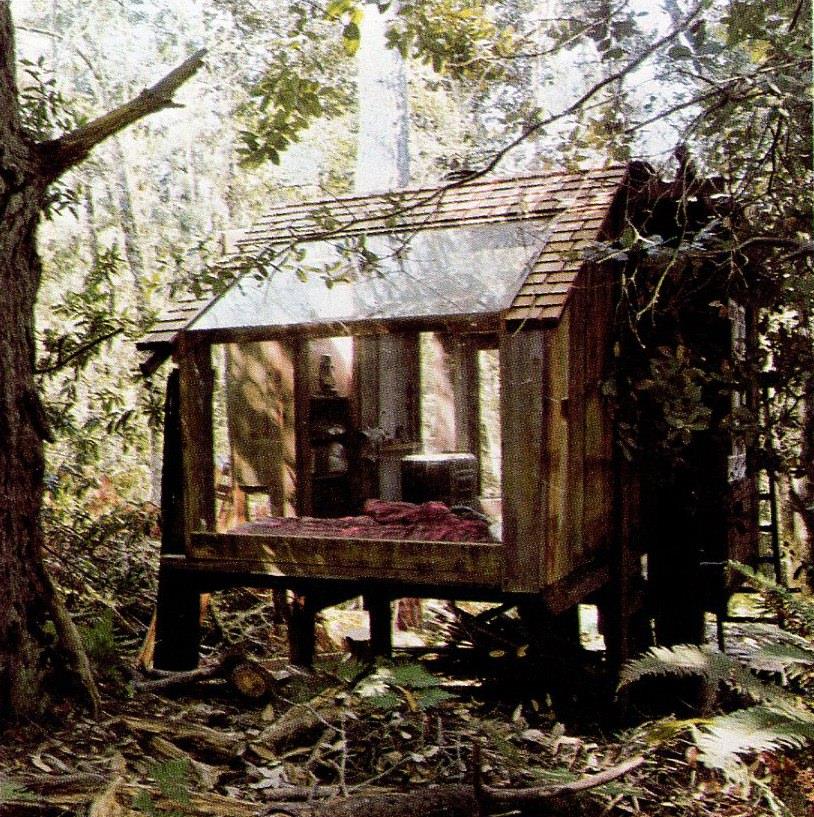

With access to land, hippietecture became rooted. Many hippie houses were hovels, but the most imaginative ushered in a fresh chapter in the “wood-butcher’s art,” celebrated in picture books like Art Boericke’s handmade house series. These places reintroduced old themes about artful design and site appropriateness, upcycling, and building with nature, values missing in the mile upon mile of Levittown-type subdivisions of cookie-cutter housing then replacing the nation’s forests and fields and marketed as “homes” to the middle class.

The architectural press, in the midst of a tizzy over the death of modernism, also took notice. Articles giving hippietecture the status of respectable architecture appeared in the finest architectural journals on both sides of the Atlantic. The July 1978 issue of Architectural Design, a provocative British journal, devoted most of itself to North American hippietecture, with the critical analysis and formal drawings – plans, elevations, sections – that legitimize formal architecture.

• • •

The tiny house movement is rooted in such precedents. As with hippietecture one must distinguish between tiny houses attached to the ground, and tiny-houses-on-wheels, which like gypsy wagons were for landless nomads.

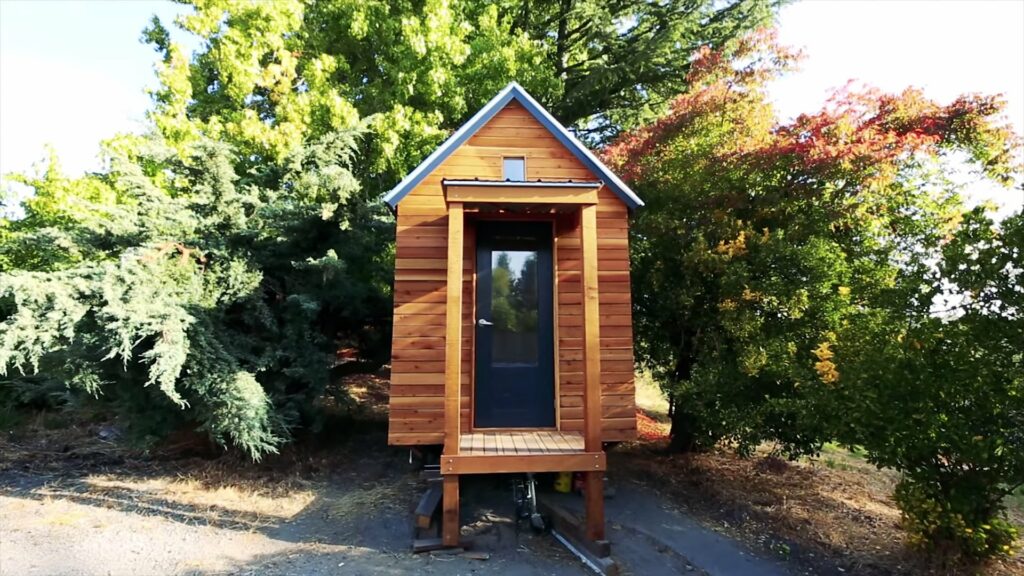

In the late ‘90s, a young man in Northern California, Jay Shafer, began building and talking about tiny-houses-on-wheels as an ethical alternative to bourgeois housing. Shafer’s an artist who understands how forms communicate meaning and materials can combine to achieve a beautiful whole. His early tiny-houses-on-wheels were cute, inviting and visually communicated “home.” At around 100 square feet, they were indeed tiny, and made minimal demands upon earth and pocketbook.

Shafer built his first tiny-house-on-wheels because he was living in his car, lacked funds, and wanted a place he could take with him when he moved. Thus, from the very beginning, the tiny-house-on-wheels became associated with relieving homelessness and with mobile lifestyle.

Shafer became the movement’s pied piper. A thoughtful fellow, he spoke about the wastefulness of conventional housing, its excessive size, the quantity of materials it consumes, the life-energy – and energy-energy — that goes into a house, the money a house requires and the sacrifice of happy occupation to produce that money. “Tiny” represented freedom from all that.

Jay Shafer’s tiny house

He also talked esthetics. He employed traditional sacred geometries. He used semiotic design gestures to focus his tiny houses on feeling like “home.” This “tiny” idea was about more than a shed on a trailer.

The new internet provided means to spread the gospel. Soon there were blogs about tiny-houses-on-wheels, where enthusiasts could share ideas and aspirations and show off their accomplishments. Those were heady times, and they continued for a decade or so.

• • •

After the Great Recession, something changed. Values of the original movement continued to be voiced, but sounded hollow. They no longer fit what was being passed-off as tiny-houses-on-wheels.

As so often happens, clever profit-motivated people saw a chance to brand products with the language of an idealistic movement and sell stuff to persons definitely not interested in living like Shafer, but convinced a scaled-down version of materially-bloated housing affirmed his values.

While the original idea was do it yourself according to your means, or perhaps hire a craftsman like Shafer to help you, now there were tiny-house-on-wheels builders, companies, and mass producers with catalogs of pre-designed house models; there were real estate types hawking tiny-houses-on-wheels; there were Airbnb tiny-houses-on-wheels where you could, they said, join the revolution for a night or two; there were reality shows to amp up the hype. Even bedrock movement resources, like Kent Griswold’s Tiny House Blog, reflected the change. The tiny-house-on-wheels had become about profit.

What had been a sparkling ideal had become just another shiny consumer product.

Even as this became obvious, the volume of praise for tiny-houses-on-wheels rose, with enthusiastic receivers of the message having no clue of the commercial deception planted in their perceptions.

There were problems commercial promoters preferred to gloss over, first among them, exactly what is a tiny-house-on-wheels? It’s on wheels, so it’s not a house. It’s an RV, a depreciating asset, licensed by the DMV, not subject to building codes or much of any other sort of building regulation, with unknown quality and dubious lifespan. When you’re putting 100 square feet of sweat-equity shelter on a used trailer, such questions matter little. But if you’re purchasing $100,000 worth of product, shouldn’t they?

The latest promotional tactic is the tiny-house-on-wheels roundup, show, convocation, jamboree, expo, or whatever you call it. San Luis Obispo just had one. They happen all over the place, with another upcoming in Boston that offers expertise on “downsizing, environmentalism, and non-toxic building.”

Three years back Mark Sundeen of Outside magazine was among 60,000 enthusiasts at a “national” jamboree in Colorado Springs. Bizarrely, he thought, this purported counter-culture event convened inside the Air Force Academy’s militarized security perimeter.

Sundeen went expecting to see the happiness, freedom and simplicity of tiny living, which he heard about from the speakers’ platform, but on going from there to the displays, he found only slick sales models with washers, dryers and air conditioners, powered by noisy generators, and staffed by smiley sales persons. “While [speakers] espoused buying less stuff,” Sundeen wrote in Outside, “what was happening across the field was the peddling of merch, all of it cool, none of it cheap.”

He looked for even one up-by-the-bootstraps tiny house, but couldn’t find one. The jamboree, he concluded, was just a trade show.

Finally, he found the only hand-built house present, all of 84 square feet built by Dee Williams of Olympia, WA. Within the movement, Williams is a female counter-figure to Shafer. Her story of giving up bourgeois living after a medical diagnosis so she could live her life on her own terms, building her tiny house, and living big is one of the movement’s treasured testimonies.

Dee Williams’ tiny home

“I’m generally skeptical about the wonders of design,” Sundeen wrote. “But being inside Williams’s house gave me a feeling of peace. Nothing fancy, nothing extra. The cedar walls hinted of contemplation. I stood with her for half an hour, talking about the freedom of owning few things.”

Williams gestured towards the sales models, rolled her eyes, and said, “Can they squeeze a clothes dryer above the dishwasher?”

Where the movement had preached that less is more, the jamboree’s message was that more is less, that you can fill a bloated tiny house with expensive stuff and still be true to the faith.

• • •

We peons are confused about housing because our housing choices are usually not really our own. The mass housing industry, which got rolling after World War II, is relatively new. Today, in places like San Luis Obispo, so-called planners have rigged things so mass housing is about all that gets built.

Thus we assign defining how we live to profit-seeking third parties, who build fields-full of generic cells to enclose generic souls, and we accept that as normal. But none of us is generic. So if we have any awareness we feel like square pegs in round holes, like frustrated souls in gyp board jails filled with stuff.

New mass-built housing is expensive, so the more’s built, the more it drives up the selling price of everything else. Life becomes a treadmill to afford housing likely inappropriate for our needs.

The tiny house’s promise was to achieve our own dream of a home place. Yet even if we build it ourselves, we may be so conditioned by the familiar inanities of production housing we lack the clarity to design our dream. So we turn that, too, over to others, consigning our home’s details and storytelling to another’s judgment, and our tiny house becomes more product than self-realization.

• • •

In the amped up hype of today’s “tiny” scene, tiny-houses-on-wheels are nothing short of miraculous. They can cure most of society’s ills, perhaps even the common cold. They can provide the housing needs of millennials and seniors, they can make the world more sustainable, they can increase diversity. Above all, though, they are affordable.

“Tiny homes make the world a better place,” according to the website of True North Tiny Homes, a manufacturer.

If such hype sounds familiar, it should, because it’s been packaged here by the noisy SLOPs (SLO Progressives) and their mayor, and used as a political hammer to allow favored types of tiny-houses-on-wheels in San Luis Obispo backyards.

As often happens, when bureaucrats and politicians get ahold of a solid idea, it gets messed up. So SLO permits the “more is less” version of tiny-houses-on-wheels and prohibits the “less is more variety” like Shafer and Williams inhabit.

Legal backyard trailers need to be relatively large – up to 400SF. For a trailer, 400SF is huge – it would be about 50-feet long. Given the city’s requirement “the unit is in good working order for living, sleeping, eating, cooking, and sanitation,” “less is more” small “tinies” are not permitted. The city’s rules not only cause size bloat, they demand equipment bloat as well.

Whoever wrote these rules, as well as the city council that enthusiastically adopted them, doesn’t understand the basics of tiny – that the idea is to provide simple affordable personalized shelter, often with shared off-tiny cooking and bathing.

Then there’s air conditioning. Everyone who inhabits a decent house in SLO knows you don’t need air conditioning, and can save eco-impact, cost and energy by foregoing it. But the city’s rules for tiny-houses-on-wheels require mechanical “cooling,” at least if your tiny is off-grid. For on-grid tinies, the rules are ambiguous.

Rules arbitrarily assume certain tiny-house RVs are superior – the kind you find for sale at an expo but not the kind at the local RV sales lot. You cannot hook up a classy Airstream in your backyard but you can hook up an ugly jumble of boxes totally lacking Shafer’s semiotic references to “home” so long as it’s cloaked in materials like you’d find on a house. SLO tinies don’t even have to be cute.

The hype becomes hilarious with claims like tiny-houses-on-wheels are perfect for seniors. The sleeping arrangements in almost all tinies involve a ladder and a low-roofed sleeping loft a stiff-jointed senior would find challenging. Can you imagine the suffering and danger your 85 year old grandmother would endure going down a ladder three times nightly to pee?

• • •

There are two legal tiny-houses-on-wheels in SLO. One, a spec-built specimen, is for sale. Zillow tells all.

The 900 square foot 2 bedroom house at 1253 Mill Street is for sale for $998,000. In the back yard is a brand new 260 square foot tiny-house-on-wheels, for sale for $118,000. It includes kitchen, bath, sleeping loft, stackable washer/dryer, air conditioning, heating and a large bamboo deck.

Construction photos show an RV on a three-axle trailer, stud built, sheathed with oriented strand board, with a loft floor of 2×6 decking. This is heavy construction for an RV that’s supposedly mobile. Moving it, due to size and weight, would probably involve a semi. It would appear this is “mobile” housing only in the sense that “mobile homes” are mobile. Move it and park. For good.

The design is quirky. Since it’s on a trailer, one must climb stairs to enter. The main level is actually on three levels, as the floor steps up in the middle to get above the trailer’s huge tires, then down again to the bath. Sleeping is in a loft.

A large part of both long walls is windows. With one of those walls facing south and no roof or window overhangs to protect from sun, or rain, those windows will overheat the interior most days of the year.

Even so, why air conditioning? The RV is all of 8 feet wide (by 32 feet long), so open windows on both sides should keep the place comfortable without a/c.

We are told this is affordable housing. Is it?

The affordable rationale goes like this: it’s a lot cheaper than purchasing a house.

OK, but it’s an RV, not a house. Doing cost comparisons with conventional RVs, this is an expensive RV.

The Mill Street tiny costs out at $454 per square foot. That cost is well into custom luxury house range, and way beyond affordable range. And unlike an actual house, the cost includes no land; that’s a monthly-rent extra.

To make a market comparison, I looked at the Toscana development off South Higuera, which at about $600,000 is priced near the bottom of the city’s new mass housing. These houses include land, conservatively worth $350,000. Factoring out land value, you end up with a 1500 square foot house at about $160 per square foot.

The premium for the Mill Street RV is near $300 per square foot.

Is this really the recipe for simple affordable shelter that will set someone free?

• • •

Jay Shafer had a moment when he got sucked into the commerce of tiny-houses-on-wheels. He founded Tumbleweed Tiny House Company, did the designs, took on a financial partner, and turned out product.

This ended poorly. He lost the company to his partner whose lawyers hounded him into poverty and homelessness.

So, Shafer has gone to ground.

He found a used trailer for a few hundred dollars. On that he built his new home, a bit less than 100 square feet. His goal was highly affordable yet beautiful shelter so light he could tow it with a car.

His new tiny-house-on-wheels cost less than $5,000, and weighs 2,000 pounds, very light for any abode. To achieve lightness, he sought the lightest materials he could imagine, then used them unconventionally.

He says it’s his simplest design yet, but took the longest to design of any project he’s ever done due to the need to pare down weight and multiply functionality in its small space. He wanted to get back to basics: showing how to live simply while addressing esthetic needs that make a place a home.

Tumbleweed Tiny House

Design, he told Bryce Langston in a web interview about this house, succeeds when stuff’s pared away till there’s nothing extra. In his new tiny house “everything is something, and something else” too. Shafer’s not yet a senior, but in his 50s he’d had enough of loft sleeping. His bed is on the main level, and is a sofa when not a bed.

Shafer’s house doesn’t include kitchen or bath – he’s parked in a backyard and shares those with the host house.

A simple well-built shelter like his is easy to maintain, heat, and cool. “A candle can heat this entire place,” he says. Cooling comes from windows.

“The selfish squandering of valuable resources and the emission of toxins without any worthwhile purpose are always corrupt and unsightly,” Shafer has written. “Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but an oversized house is an ugliness we all have to contend with.”

“Trying to boil things down to the essence is what it’s all about.”

Shafer has a back-to-basics dream. It’s a community of simple houses like his with a shared community building containing baths, a kitchen, and social space. A community of people set free by their tiny houses.

Given the bourgeois pretensions of San Luis Obispo’s notions about tiny-houses-on-wheels, his dream would not be welcomed here.

Costing out a tiny

To get a sense of what a factory-built tiny-house-on-wheels RV like those permitted in SLO might cost, I went to Tumbleweed Tiny House Company’s website, which has a price list for “designing” a tiny.

I chose their classic pitched-roof wood sided Elm model, 30’ feet long. It’s fairly basic inside, and I resisted fancy upgrades like propane heat or a washer/dryer or composting toilet. Still, you can see why manufacturers say “prices starting from …” once you go through the process. Here goes:

Base price (“starting from”) $87,000

Natural wood siding, an esthetic “cuteness” splurge $3,500

2 skylights to brighten the interior $3,000

Kitchen “upgrade” to get an oven, and a sink large enough to function $2,400

Heat and a/c (Tumbleweed only offers heat with a/c in a combination package; in SLO you could get along without heat beyond a portable heater, but the city doesn’t permit that) $2,400

Total for this 250 square foot all-electric RV $98,300

Then there’s this that’s also required:

Handling $780

Freight to SLO $4,000

Sales tax $7,127

Grand Total for RV’s arrival in SLO $110,200

In addition, there’s the cost of site preparation and hookup, which the city estimates at $15,000, various DMV fees, permits, and other miscellaneous costs of installation and landscaping. Conservatively we’re looking at $130,000 for this RV, about $520 per square foot.

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines