Who win$ if state controls Paso Robles water basin?

March 27, 2016

Editor’s Note: This is first in a two-part series examining economic rewards tied to North County water. Cindy Steinbeck’s letter is at the bottom of this article.

By DANIEL BLACKBURN

A quiet but frenetic land rush in the North County fueled by rich and generous investors suggests that underground water, not wine, may be the region’s real jackpot. And evidence shows that the potential for astronomical reward for a few would be greatly enhanced should the state assume management control of the huge Paso Robles aquifer.

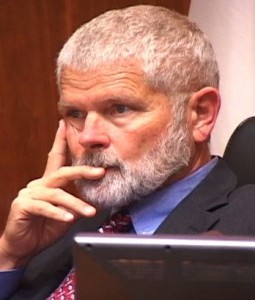

Relinquishing authority over the groundwater basin has become the immediate goal of two San Luis Obispo County supervisors, Adam Hill and Bruce Gibson. Both politicians began actively advocating for state management of the Paso Robles resource in the hours following the recent defeat by voters of a proposed water district; both, however, vocally endorsed “local control” before seeing the electoral results.

Gibson subsequently chided North County voters for “putting the county in an untenable situation” after the district proposal was crushed, and suggested that county management of the basin would be too costly.

California law requires that water basins be sustainably managed by local agencies or risk intervention by state water officials.

Hill’s and Gibson’s sudden transformation into outspoken state-takeover proponents has closely mirrored behind-the-scenes maneuvering by powerful external factions seeking control over the basin resource.

Prospective benefactors of a state-controlled basin include Beverly Hills billionaire Stewart Resnick, whose agricultural empire of more than 3 million acres in the Americas; Harvard College’s $37.6 billion endowment management “parent” company, Phemus Corp.; major state water providers, both public and private; and at least several well-placed local residents.

Resnick, through his wholly-owned The Wonderful Company, has been purchasing multiple acreages in the Paso Robles area, starting in 2012 with acquisition of the 750-acre Hardham Ranch on the southeastern edge of Paso Robles. The ranch, which for decades had been used for grazing and dry farming, was quickly covered by miles of new grapevine plantings, deep wells, and huge lined storage reservoirs. The ranch has been deeded to a new Resnick company, Roll Vineyards LLC.

Resnick controls huge water bank

Resnick owns, among numerous other entities, POM Wonderful, Fiji Water, Paramount Farms International, and Justin Wines in Paso Robles. He is famed for his domination of pistachio, almond, pomegranate, and citrus agribusiness in the Central Valley, and along the way has commandeered most of the water rights in that region with the Kern Water Bank.

Resnick is also known for replacing water-stingy seasonal crops with year-around crops requiring constant irrigation. And he has found a way to guarantee that will be possible.

Paramount Farms International is the primary participant in the Central Valley’s unique “water bank,” the “biggest in America, if not the world,” according to Businessweek.

In 2014, the magazine described the Kern Water Bank: “It occupies 32 square miles in Kern County, making it larger than Hollywood and Beverly Hills combined; it extends across the main highways that run through the San Joaquin Valley and alongside the California Aqueduct. The bank itself is a network of 70 man-made ponds, a six-mile-long canal, and 33 miles of pipeline that captures rain and snow-melt from the Sierra Nevada range and can be fed by water purchased from the federal and state governments as well as local sources. In 2007, prior to three straight dry years, the bank held 1.5 million acre-feet of water, creating a stranglehold on the historically-dry region’s most treasured resource.”

That same Businessweek article described Resnick and his wife Lynda as “quintessential Beverly Hills billionaires, with a sumptuous mansion and a new $54 million pavilion named after them at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.”

They also own and farm 188 square miles — 125,000 acres — in the Central Valley, an area more than four times the size of San Francisco.

The Central Valley region’s water supplies once were under management by the state’s Department of Water Resources, but in a complicated and almost-covert maneuver now known as “The Monterey Accord,” Resnick was able to assume control of those water rights.

Resnick’s water bank in the Central Valley “was established under particularly sketchy circumstances, and is no stranger to lawsuits ever since the Resnicks – through Paramount Farms – began buying up area land and water rights ‘Chinatown-style’ in the 80s and 90s,” a 2011 research project asserted.

That study, by Grace Communications Foundation, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit, noted that after Resnick claimed these water rights with the land purchases, he and other wealthy landowners created the water bank — using public funds.

That “gave them them unlimited withdrawals and the ability to resell water for big profits, neglecting nearby residents (who were) without clean water access in the process,” the foundation’s report concluded.

A former Bakersfield resident and Resnick employee, Sue Luft, was an outspoken supporter of the defeated water district plan, but now has shifted her attention to lobbying for a third supervisor’s vote authorizing a state takeover of the basin’s management. Luft and her husband own a small Paso Robles vineyard.

North County voters’ fear of the inevitability of a water bank in the Paso Robles basin — one of the largest aquifers west of the Rockies — was a key factor in the district proposal’s rejection. So was a growing recognition on the part of local residents that an aquifer’s real value is in its capacity, as well as the actual water it may contain.

And finally, many questions went unanswered about the motives of the people who sought leadership roles on a new water district’s board of directors.

The East Coast influence

Equally aggressive with recent North County land purchases is a derivative of the wealthy Harvard College endowment, the Harvard Management Company, Inc. (HMC) of Boston.

Despite apparent efforts to obscure local buying activities through an interconnected string of companies and LLCs, HMC has accumulated significant acreage in the Shandon area and elsewhere, often paying premium prices for the land.

Harvard College’s endowment fund’s parent company is Phemus Corp., and several of its subsidiaries have been busily locking up local land and accompanying water rights. They include Brodiaea Inc., Bellum LLC, Monardella LLC, and SLO San Juan Road LLC.

This curious acquisition apparatus is questioned by Cindy Steinbeck, whose family has farmed wine grapes in the North County for decades, and who leads an effort by several hundred other landowners seeking quiet title to their groundwater rights.

In a probative March 8 letter, Steinbeck told Stephen Blyth, president and chief executive officer of HMC, that “the use of so many layers of LLCs when they are all different alter egos of Harvard is one thing that causes me concern, as it seems designed to obfuscate Harvard’s activities in this area, camouflaging who actually owns the land.”

While Harvard’s North County investments may be notable both for the price the land is fetching, and for the number of acres being gobbled up, the physical location of the properties may be the most remarkable element of the transactions.

In an area specified in 2008 by San Luis Obispo County water officials as a potential location for a water bank, Harvard’s HMC has purchased property through two of its entities — Brodiaea and SLO San Juan Road. That property happens to be the location of the only turnout in the North County for eventual supplies from the State Water Project (SWP).

Now, after years of delay, that turnout structure is being constructed, at taxpayer expense.

SLO San Juan Road just months ago also purchased a significant parcel east of Paso Robles from the Arciero Vineyard Group — an area the county asserts is particularly impacted by groundwater shrinkage.

Harvard’s local agent is Matt Turrentine, who with his partner James Ontiveros has been providing real estate direction to the Boston investors. Turrentine is a board member of the Paso Robles Agricultural Alliance for Groundwater Solutions (PRAAGS), the primary proponent of the failed water district proposal.

Steinbeck suggests that Harvard’s local investments have been motivated by what it perceives as “an emerging water market” in California.

“The local perception, right or wrong,” Steinbeck wrote in her letter to Harvard CEO Blyth, “is that Harvard has been doing the following: making purchases using multiple layers of disregarded entities such that it would be difficult for the layperson to trace the purchase back to Harvard; using agents to push for formation of a local water district that would allow Harvard’s properties to ultimately benefit from government grants and taxpayer funds; inducing certain property owners to sell with offers that are many times the going market rates and using this method to acquire properties that contain public water infrastructure; and generally not being forthcoming with the local populace about how these investments could affect the most vital of resources—all in the name of returns on investment.”

A large majority of North County landowners apparently agree with Steinbeck’s analysis.

Next: Exploitive, tax-free investments are under federal scrutiny, and some key Harvard money managers are resigning.

Cindy Steinbeck’s March 8 letter to Harvard Management Company President and CEO Stephen Blyth:

“I am writing because I am concerned about recent activities by the Harvard Management Company, Inc. (“Harvard”) and its related entities within the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin in northern San Luis Obispo County, near the central coast of California. As a fifth-generation resident in this area, I am seeking some explanation from your organization as to the purpose and intent of your “investments” in my community. Here are my concerns:

“It is my understanding that the endowment for Harvard College (valued at $37.6 billion in 2015) is managed and invested through your organization and a related parent company called Phemus Corporation. According to Form 990s filed with the IRS on behalf of Phemus Corp., Harvard owns or controls a number of different LLCs and corporations. The particular companies in which I am interested have been transacting business in the Paso Robles area. They are Brodiaea, Inc., Bellum, LLC, Monardella, LLC, and SLO San Juan Road, LLC.

“These companies appear to be interrelated. In recent tax filings for Phemus Corp., Bellum, Monardella, and SLO San Juan Road are listed as “disregarded entities,” meaning that these are single member LLCs that, for tax purposes, are disregarded as being a separate entity from the member—in this case, ultimately, Phemus Corp. Brodiaea is listed as a related corporation; however, tax filings for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2014 show that Brodiaea is 100% owned by Bellum which, in turn, is controlled by Monardella which, in turn, is controlled by Phemus Corporation. Oddly, the Business Directory of Massachusetts lists Bellum as having two members, Monardella and SLO San Juan Road, while the California Secretary of State shows SLO San Juan Road as having one member/manager: Bellum. Regardless of the actual structure of these LLCs, it seems indisputable that each is ultimately owned and controlled by Harvard. The use of so many layers of LLCs when they are all different alter egos of Harvard is one thing that causes me concern, as it seems designed to obfuscate Harvard’s activities in this area, camouflaging who actually owns the land. Accordingly, my first question for you is why are so many different shell entities involved?

“Public records show that Brodiaea first began buying ranch and vineyard land in northern San Luis Obispo County in July of 2012, and has steadily acquired land each year since. What is particularly interesting about Brodiaea’s purchases are that they were of unlisted properties, and the local wisdom is that Brodiaea may have paid well over the going market price per acre. Phemus’s tax filings show Brodiaea’s assets as of June 30, 2014 to be $132,885,644.

“Alvaro Aguirre, former Managing Director of Natural Resources for Harvard Management Company/Phemus, was listed as the Executive Officer and a director of Brodiaea on SEC Form D. Brodiaea lists its agent for service of process in California as Matthew Turrentine. Locally, Mr. Turrentine is the face of Brodiaea and also an active board member of a group called Paso Robles Agricultural Alliance for Groundwater Solutions (PRAAGS), which is spearheading the effort to form a special act water district over the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin. The formation of a water district would, among other things, open the door for future water brokering and banking in the Paso Robles groundwater basin.

“The proposed district would also be eligible to apply for California Proposition One tax bond monies to fund groundwater storage projects. In addition to having the ability to meter, assess and fine local residents for groundwater extractions. The formation of this water district is a matter of great concern to the many local residents of the basin, who oppose the creation of such a large bureaucracy with such far-reaching powers. It is very troubling, then, that Brodiaea/Harvard would, immediately after starting to buy land in the area, become involved in the endeavor to form the water district via its local agent. Accordingly, my next questions are whether Harvard supports the formation of the water district, and, if so, whether Harvard has contributed any money to that cause, directly or indirectly, or directed its local agent(s) to support that cause, financially or otherwise.

“The land that Harvard has invested in through both Brodiaea and SLO San Juan Road is located near Shandon, California in very close proximity to the Coastal Branch of the California State Water Project (SWP) aqueduct. In 2008, the County of San Luis Obispo identified this area as a potential location for a water bank in a Water Banking Feasibility Study. The banking feasibility study recommended that specific “banking partners” be identified who might be interested in storing water in the basin or using banked water. The targeted location of Harvard’s purchases around the SWP pipeline and near the area identified for future water banking is especially concerning when I hear that Harvard paid many times the going market rate for these properties. My family has been farming grapes for 5 decades in this region, and such an investment does not make economic sense (particularly in the Shandon area), if your intent is simply to grow and sell grapes. It would, however, make perfect sense if the investment wasn’t for farming but rather for the brokering of water and/or storage space in the aquifer. This begs the following questions: Why did Harvard choose the land in the location it did? Why did it endeavor to purchase unlisted properties near the SWP, properties that were not known for producing particularly valuable grapes? Was Harvard aware of the location of the SWP pipeline and the SLO County Water Banking Feasibility Study before purchasing these properties in Shandon?

“Perhaps even more concerning than the Brodiaea purchases are the recent purchases by SLO San Juan Road, LLC. According to the Delaware Secretary of State, SLO San Juan Road was formed on December 6, 2013. Thirteen days later, it closed escrow on a previously unlisted piece of property along San Juan Road which just happens to be the location of the planned SWP “turnout” for the town of Shandon—and the only place in Northern SLO County where state water will be pulled out of the pipeline. The turnout had been part of the plans since the initial construction of the SWP pipeline in the mid-nineties but, despite several false starts, had never actually been built. Following Harvard’s purchase of the property, the dust was knocked off the plans and the turnout is currently being constructed at taxpayer expense. At the same time it purchased the turnout property, SLO San Juan Road also purchased the property above it, a piece of vacant grazing land that contains the town of Shandon’s only water tank. Neither property has a history of grape production, or has even been irrigated recently. Tax filings by Phemus put SLO San Juan Road’s assets at $2,674,634 as of June 30, 2014 but, again, I hear that the price paid for the properties was much more than that. Regardless, I would like to know the following: Was Harvard aware of the planned turnout when it offered to buy that particular piece of property? Why did Harvard choose to buy the properties containing most of Shandon’s important water infrastructure? Did Harvard have any role in urging the County of SLO to finally construct the turnout, which will bring state water into the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin for the first time?

“Near the end of 2015, SLO San Juan Road went on another buying spree, acquiring a host of parcels immediately to the east of the City of Paso Robles from Arciero Vineyard Group. This is an area that the County claims is suffering from severe groundwater declines, yet Harvard is making a substantial investment that others have been afraid to make. My question here is, what does Harvard know that others don’t? And furthermore, why purchase these properties — which do have a history of successful grape production — through SLO San Juan Road, rather than through Brodiaea, which purportedly was created to be Harvard’s vineyard investment vehicle?

“As I am sure you are already well aware, a group of landowners in and around the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin calling themselves Protect Our Water Rights (POWR) filed a legal action in November 2013 seeking to quiet title to their groundwater rights. As the Quiet Title action has proceeded through the Santa Clara County Superior Court, Mr. Turrentine, along with his attorney, has occasionally attended hearings in San Jose, CA. This is curious behavior for someone who is not a party to the action—indeed, no other non-party has bothered to make the 3 hour drive to see the hearings—and it seems to indicate that Mr. Turrentine and/or Harvard has a keen interest in what will happen to groundwater rights in the area, and are not simply interested in growing grapes. If Harvard wanted to protect its groundwater rights for future vineyard irrigation it could, of course, join the Quiet Title action, as hundreds of other landowners have. The Quiet Title action, however, may be adverse to those who hope to sell or trade their water rather than irrigate with it.

“Incidentally, during a Board of Supervisors meeting in early 2015 where important water matters were being discussed, your agent Mr. Turrentine and his partner Mr. James Ontiveros asked to speak with me “in the back” through a text on my cell phone. I didn’t reply, nor did I go to the back. They proceeded to the front of chambers at the next break and aggressively threatened legal action if I didn’t stop questioning Harvard’s intentions with the land in Shandon. My attorney stepped in and kindly asked them to let her know what false statements I had made that would warrant a legal action against me, as well as asking them to provide her a written statement of exactly what Harvard was doing, so that we could be sure and make only correct statements in the future. To date, no such information has been provided to my attorney.

“In August 2015, I sent a letter to the California Water Commission, the board responsible for allocating $2.7 Billion dollars of Proposition One bond money for water projects in California. (A copy of that letter is attached for your reference.) The letter questioned how California can allocate money to quasi-governmental agencies for underground storage when the state has no additional surface water to store underground. The letter strongly suggests that allowing profiteering by the exchanging, banking, and in lieu wheeling of state water would be akin to fraud, because the surface water that supplies the SWP is over five times over allocated and oversold. Mr. Alvaro Aguirre and Ms. Kathryn Murtagh were copied on the letter because I wanted them both to be aware of these concerns if they were investing in the Paso Robles area with the hope of participating in a water market here. I am positive it is unrelated, but I was disturbed to learn that Mr. Aguirre resigned approximately one month later, after 12 years with Harvard, and that the man who was tapped to replace him as the manager of the Natural Resources portfolio, Satu Parikh, also resigned.

“I recently read the article entitled Rich Schools Queried by U.S. Lawmakers on Endowment Spending dated February 9, 2016 by Janet Lorin for Bloomberg Business. It appears that two congressional committees have opened an inquiry about how the wealthiest schools manage and spend endowment funds. Harvard is named as being one of the schools to have received such a letter. It appears that Congress is evaluating the value of federal policies that permit (1) tax-free investment earnings for schools, (2) tax deductions for donors in light of the fact that Harvard and other institutions “supply limited information about their endowments on Internal Revenue Service forms…”

“This congressional inquiry is troubling but perhaps timely in light of Harvard’s recent activities in the Paso Robles region. I realize that there may be a very reasonable explanation for every action that Harvard has taken, but the local perception, right or wrong, is that Harvard has been doing the following: making purchases using multiple layers of disregarded entities such that it would be difficult for the layperson to trace the purchase back to Harvard; using agents to push for formation of a local water district that would allow Harvard’s properties to ultimately benefit from government grants and taxpayer funds; inducing certain property owners to sell with offers that are many times the going market rates and using this method to acquire properties that contain public water infrastructure; and generally not being forthcoming with the local populace about how these investments could affect the most vital of resources—all in the name of returns on investment. This is not behavior that befits an institution of Harvard’s stature.

“If Harvard’s investments are at all motivated in anticipation of an emerging water market in California, I encourage you read the recent article in the Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal by Adam Keats and Chelsea Tu entitled “Not All Water Stored Underground is Groundwater: Aquifer Privatization and California’s 2014 Groundwater Sustainable Management Act.” (9 Golden Gate U. Envtl. L.J. 93 (2016).) Mr. Keats and Ms. Tu’s law review article makes a very important query: “With local interests being given the responsibility — and the power — to regulate ‘their’ local groundwater basins, the question is: how effective will local agencies be in meeting the sustainability goals of the Act, especially when long-term sustainability may directly conflict with a corporation’s short-term profit goals?”

“Viewed in light of the points made in that law review article, the information I have provided to you above causes me to question Harvard’s commitment to environmentally and socially responsible investment practices in its Natural Resources investments in the Paso Robles region. I believe it is Harvard’s responsibility to disclose its intentions to the local populace in Paso Robles, and I eagerly await your response.”

The comments below represent the opinion of the writer and do not represent the views or policies of CalCoastNews.com. Please address the Policies, events and arguments, not the person. Constructive debate is good; mockery, taunting, and name calling is not. Comment Guidelines